This story describes how a repressed traumatic memory was triggered and resurfaced three decades after the event, and it explores the impact of this repressed memory on friendships I’ve cherished:

DC-8

On April 16, 1998, while in Houston, Texas, I was working as a radar air traffic controller for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) at Houston International Airport (IAH). I was fifty-three years old.

The ceilings and visibilities were very low in the area. I was very busy working fourteen jets inbound to Houston Intercontinental Airport when it was brought to my attention that a four engine jet cargo plane I was working was 500 AGL (above ground level), in the clouds, and still descending towards the city of The Woodlands (15 miles north of the airport).

After transmitting to the pilot four times, the pilot finally stopped his descent at 200 feet. I thought this jet was going to crash into the city of The Woodlands!

After I talked the pilots down using a radar approach to a safe landing at Houston, I was relieved off my position to write a statement. I immediately ran outside of the building and vomited . Later you will see a pattern – a psychological one.

During my thirty-seven year career I worked over twenty-five emergencies requiring a Radar Surveillance approach. I never remembered vomiting after working one of these emergencies.

See the attached PDF for a more complete story on this DC-8:

PDF: DC-8 – Flight Assist

Following the DC-8 incident, I returned home only to be haunted by recurring nightmares of an emergency 30 years before in Amarillo, Texas, back in 1968.

I found myself in what I thought was a nightmare, right at the start of my radar training—only 15 minutes in. The dream felt like the most unbelievable aviation story ever. It surpassed anything Hollywood could imagine: H-bombs and a rookie like me, tasked with an emergency radar approach landing with just a few minutes of radar training? Utterly absurd!

After enduring three restless nights, my wife posed a question that struck me: “How can you be certain this event never occurred? Are any of your fellow air traffic controllers from that day still around?”

Prompted by her inquiry, I scoured the internet and unearthed the phone number of Bobby Jones, my radar instructor. Despite our friendship, I hadn’t reached out to him since departing Amarillo in 1969.

Upon answering the call, Bobby’s immediate reaction was, “Why are you reaching out after thirty years?” I inquired if he recalled a T-38, with the callsign “Brusk 11.”

To my astonishment, Bobby did! What I had dismissed as a dream was, in fact, a repressed traumatic memory that had lain dormant for over three decades. It was the aftermath of that first emergency that had me reeling outside, sick to my stomach.

This is similar to my other blog posts, where I’ve included written documentation or audio/video interviews with the individuals involved. Here’s the 4-minute recorded interview with Bobby Jones (1936 to 2012), conducted shortly after we made contact on April 20, 1998:

T38

Bobby was my radar training instructor that day, but was in the restroom when most of this emergency occurred. What is not on the tape is that the only controller in the radar room (George) froze and wouldn’t talk to the pilot after he vectored the T38 (call sign Brusk 11) into a severe thunderstorm.

The pilot on emergency frequency was actually screaming, “Mayday, Mayday, lost the canopy, one engine out, student pilot injured, request vectors (headings) back to Amarillo Air Force Base”. George just sat there screaming, “shit, shit, shit!”Unanswered the pilot transmitted, “we are ejecting!” At that point someone had to do something, so I transmitted, “stay in the aircraft you are over the city, turn right heading 270!”

When I issued the vector to the airport, the pilot screamed as if he were in pain ! He wouldn’t transmit after a few requests, so I had him ident on his transponder (this was before we had altitudes displayed on radar). I gave no-gyro (telling the pilot to turn or stop turning) headings for a left downwind to Runway 21.

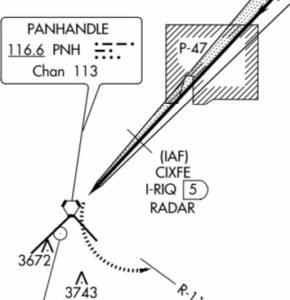

A few minutes later, George moved his chair next to mine. I smelled alcohol on his breath. He said, “good job Clint, but whatever you do, do not let him fly over Pantex (See Prohibitive Area P-47 at the bottom). He will kill us all if he crashes !” That was all the help I ever got from George.

I knew the Pantex Plant made Nuclear Bombs; however, the public was not aware back then because it was“Top Secret”.

At that moment my belief was if he crashed into the Pantex plant and set off the H-bombs, the explosions could kill everyone in the North Texas area or worse! My knees were jumping up and down uncontrollably against the radar console.

I knew the T38 was in bad shape and it was doubtful if this approach didn’t work that there would not be another opportunity. I needed to align the aircraft at least 10 miles from the runway to ensure an accurate alignment to the runway centerline . I couldn’t do that without overflying Pantex. I had to make a big decision- the pilot’s lives or the public’s.

I turned the T38 inside of Pantex, which endangered the pilots, but I luckily lined the T-38 up with the runway. I then had the pilot descend the aircraft to 400 feet above the ground. The pilot reported by transponder when he saw the runway a mile out at 500 feet above the ground. At the same time a controller in the control tower was in my headset telling me that he saw the T38 come out of the clouds and Bobby Jones was standing behind me screaming, “What in the f*** are you doing?” I unplugged, ran outside the building, and threw up into the grass next to the building entrance.

Ten minutes later, I took sick leave and went home. Bobby Jones called a few hours later and told me that he and a supervisor had driven on the closed runway to view the T38. He stated that the cockpit was exposed to the elements, no canopy, full of water, and hailstones the size of softballs. The student pilot had been knocked unconscious by a hailstone and the pilot was suffering from hypothermia.

If the pilot had ejected he would have killed the student pilot. Bobby surmised the pilot was getting electrically shocked in water up to his neck when he transmitted, so that’s why he stopped transmitting , and at that point he could not longer see his instruments.

The T38 had holes in the vertical stabilizer and in both wings. Both jet engines were missing turbine blades. Only one engine was working. The T38 never flew again.

There was a coverup by the Air Force and FAA on this incident. I was never interviewed by the US Air Force Accident Investigation Team.

Unfortunately, my unconscious repression of this memory resulted in the weakening of two significant work friendships. I subconsciously avoided anything or anyone that might trigger that memory. Nonetheless, in 1998, I managed to mend these bonds after employing the “Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM) procedure,” that was initially utilized by me in 1984, to address a different traumatic incident at work. This approach was pivotal in my healing process.

https://clintmatheny.cdn-pi.com/how-i-cured-my-ptsd/

The public was unaware of the nuclear arsenal at the secret Pantex Plant until 1990, following the end of the Cold War. That year, Prohibitive Area P-47 was indicated on aeronautical charts, disclosing the facility’s actual function. Similar to its status in 1968, Pantex remains the sole site in the U.S. for the manufacture and disassembly of nuclear weapons.

Clint77090@gmail.com