After my previous post, I had many request for more air traffic controller emergency stories. This somewhat violates my purpose for the blog, so these are my last posts on this subject. Maybe someday I might make a separate website for my other FAA experiences. I am also a licensed pilot as are approximately twenty percent of FAA air traffic controllers.

All five of the emergencies below had successful outcomes. One was an airliner with a total electrical failure at night in weather with my future wife. The chances of a jet airliner having a complete electrical failure are one in 100 million operations. I am not sure of the odds for an air traffic controller working his future wife on an airliner with an electrical failure.

Coffee, Tea, or a Flashlight?

My wife, Laurie: “ I was married to Clint for six years when one evening in 2012, I walked into our home office and saw that he was clearing out his file cabinet. On the floor was a pile of papers and to my shock was a FAA Flight Assist Report dated December 4, 2001. I was the first class flight attendant on this Continental Airlines Boeing 737-500 on that December night. Until that night we had no idea that our lives were connected that night five years before we met. Small world!

This is what happened from my viewpoint: We were about twenty minutes out from IAH when I entered the cockpit with their coffee. Almost immediately the cockpit lights went out, to include all glass flight instruments. The first officer tried to retrieve the cockpit flashlight but was unable to pull it out of its holder. I gave them my mini flashlight out of my apron which I always carried on the night flights. I had never seen a cockpit go completely dark in the thirty years I had been a flight attendant. I was at one time a private pilot and knew we could be in trouble. I asked only one question, “will you give us an “Easy Victor” (code for evacuation) captain”? The captain simply said, “yes”. I left the cockpit and made preparations for landing. Except for the emergency exit lights, the lights in the cabin were also out!

About 30 minutes later we landed without incident and when we got to the gate the pilots stayed an unusually long time in the closed cockpit. I waited for my flashlight and when they walked out they were so sweaty wet that you could see their skin through their shirts. They were definitely stressed! ”

My Story: I was in the break room and I was told to report to the Radar Room to do a radar approach (talk down) with a B737. I was told by the supervisor that the B737 was having navigational equipment problems. I was not aware of an electrical failure until I was briefed by the controller who had been working the flight.

Note: A Boeing 737/5 has a standby battery that will last only 30 minutes (meaning: after 30 minutes no radio & no navigation equipment).

I was the only controller on duty out of twelve others that knew how to conduct a radar approach (see PDF below). That night we had an overcast ceiling with base of the clouds at 700 feet and the visibility was 4 miles!

Laurie should have gotten an award for her mini-flashlight. The pilots needed a light to see the only instruments that were working.

Side story:Laurie had some bad emergencies in her career: one plane crash where one passenger died and one hijacking in 1974, where a mental patient on leave from a VA hospital put a knife to her throat an hour outside of LAX. She talked him into dropping the knife and surrendering in the LAX terminal lounge (she stated that the scariest part was all of the law enforcement people had pointed their guns at them). The picture above was taken on the day she retired after 38 years with Continental Airlines.

My son Clay, is one of the few controllers that knows how to conduct a radar approach and he works at the FAA Terminal Radar Facility at IAH (where I retired).

A Swiftair B737 lost all instrument displays in 2017 after departing Shannon, Ireland. They were fortunate that the weather was good.

Is This Going To Be A Fatal Accident?

Around 9 pm on February 18, 2000, a Beechcraft Bonanza N89E during very low deteriorating ceilings (below 300 feet) and visibility weather conditions (1/4 mile) had attempted two ILS approaches, but was unable to navigate on the final. He then told the controller he only had 25 minutes of fuel left.

The supervisor called me down from the break room to conduct a unpublished Radar Surveillance Approach (just like I did with the B737). Before my headset plug could entered the radio jack, the controller said, “he just ran out of gas”! I didn’t have a chance to react when the controller grabbed my headset plug and plugged it into the position jack, jumped out of his chair, and the supervisor said, “Clint do something!”

I knew he was going to collide with an object below him and the slower and more under control the aircraft was, maybe they could survive; however, just by me telling the pilot to stop his turn put some of the responsibility on me. He was going to hit something immediately after popping out of the clouds! I put the aircraft in that direction when I told the pilot to stop his turn. Was this another example of synchronicity or me being at the wrong place at the right time?

This is a 2 minute audio on Bonanza 89E

My heading took the plane into the second story of the bedroom window. A four year old boy’s bed backed up to the window and the year and a half old baby boy was on the other side of the room. The four year old would have been killed if he would have been in his bed. The four year old boy had never stayed up beyond 9 PM until that night. The crash took place at 10 PM.

The pilot of N89E phoned me two weeks after this event. He appreciated me telling him to fly his airplane, because he was distracted trying to restart his engine. The pilot told me that didn’t receive any injuries when he crashed into the upstairs bedroom. The worst part of the crash was that the airplane’s center of gravity made the plane fall out of the window to the ground. Getting out of his plane he dropped his owners manual on the ground. He received a minor cut on his hand picking up the manual by a piece of glass that had fallen into the grass from the upstairs window. That was his only injury. Not even a bruise. I asked the pilot what he did for a living. The pilot told me he was employed at NASA as a space physicist!

“Departure I’m losing an Engine”

I left employment with the FAA in 1981 and started a business with a coworker. I kept the business, but I returned to my previous FAA facility eighteen months later. On my first day back in retraining I was busy working over ten other aircraft in the Houston area when Cessna 56T a single engine Cardinal airplane pilot told me that his engine had stopped. He was in the clouds below 3,000 feet descending over the TV antenna farm that are 2,049 feet tall. My trainer later told me to start collecting my Flight Assist documents and write a book! What transpired is also on the 3 minute audio:

On February 4, 1998, at 8 a.m., three US Navy FA-18 Hornet fighter jets left Jacksonville NAS in Florida, heading to Ellington Field in Houston. The pilots were unaware that they would encounter thunderstorms along the way, forcing them to divert their course and depleting their fuel. To make matters worse, the primary navigational aid for landing, the TACAN, was out of service. They also did not anticipate that the weather conditions would be much worse than predicted. The ceilings were below 500 feet and the visibilities were 1 mile or less within a 150-mile radius.

Having worked with US Navy fighters before, I knew that they lacked the civilian Instrument Landing System (ILS) panel. This $12,000 instrument could have been a lifesaver, but the Navy bureaucracy neglected to equip its aviators with it (see PDF Letter to Senator John McCain). It was a perfect storm for a disaster.

At 10 a.m., I was on the South Radar Position, which covered Ellington Field. I received a radar handoff from 30 miles east and wondered how they would land. The ceiling was 400 feet and the visibility was 1/2 mile, with drizzle and fog (the best weather in the Houston Airspace). I immediately contacted Beaumont on a landline to check if they had better weather. They did not.

The flight leader contacted me from 25 miles out and I asked him, “The TACAN is out of service, did you get the weather, and what are your intentions?” He replied, “Please vector us to the Gulf to eject. We have less than twenty minutes of fuel. How far to the water?”

The ceiling and visibility were so low that it was doubtful that the US Coast Guard helicopters could rescue the pilots if they ejected into the cold Gulf waters in February.

I asked, “Will you accept an unpublished Radar Surveillance Approach that might require us to break minimums to land?” He agreed. I directed the formation to an eight-mile final, lowered them to 400 feet, and then to 300 feet (200 feet above the ground) at one mile from the runway. They spotted the runway at 1/2 mile final and landed safely.

I was told that one F-18 ran out of fuel on the taxiway. I saved the Navy’s three FA-18s, worth $87 million ($29 million each), and possibly prevented injury or death to three pilots.

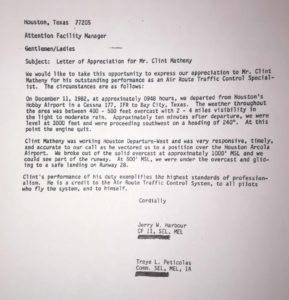

Most controllers work for over thirty years without having to talk a pilot down to the runway. The letter below documents six aircraft emergencies in an eleven-month period, including the three F-18 Hornet fuel emergency. I retired from the FAA in May 2004.